Grade 5.1.1.5

Sailing west, Columbus Asia , and the land is named for another navigator.

In the port of Palos August 3, 1492 , three ships, carrying ninety men under Columbus Santa Maria Canary Islands , off the coast of West Africa , the ships were refitted. When they took to the sea again, the date was September 6, 1492 .

Now, if the calculations of Columbus Japan Spain

The grumbling grew worse. The crews met secretly, declaring that Columbus Spain Columbus Columbus Columbus Columbus

THE FLEET NEARS LAND

On the afternoon of Thursday, October 11, there came a change. A green branch was sighted in the water, and then a green fish of the kind found near reefs. A stick, skillfully carved, was fished from the sea, and a sailor saw a thorn branch with red berries that seemed to be freshly cut. Even Columbus

About two hours before midnight , standing on the deck of the sterncastle, Columbus

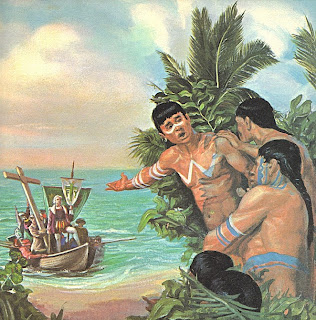

Throughout that night the ships waited for daylight. The first rays of the rising sun on Friday, October 12, 1492 , revealed the tree lined coast of Wading Island in the Bahamas Columbus

The sailors knelt in thanks to God. Some could not hold back their tears of joy and others kissed the ground. Columbus San Salvador Columbus

A brisk trade developed between the sailors and the Indians, who came loaded down with skeins of spun cotton, parrots, and darts. Everything the Indians offered, Columbus

Still certain that Japan Columbus Hispaniola (now Haiti Dominican Republic

Bad news awaited Columbus Hispaniola . His fort was burned and his colonists had disappeared. Building a second fort and founding the city of Isabella Columbus Columbus Columbus Far East .

In all, Columbus South America and many important islands, among them Cuba Jamaica May 20, 1506 , Columbus

But another Italian navigator of the day, Amerigo Vespucci, realized that these lands were not part of Asia . Between 1497 and 1504, he may have made as many as four voyages to the New World and claimed to be the first explorer to set foot upon the continent of South America . A map, published in 1507, gave the name of America South America . Later geographers gave the name to both continents.

By: Earl Schenck Miers

Paintings: Alton Tobey

No comments:

Post a Comment